New York Times – Sunday Book Review

By: Joseph Kanon

Published: October 28, 2007

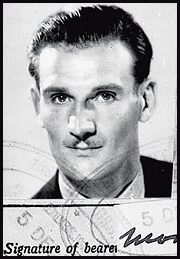

It’s rare that a single war story inspires two books in the same season. But even by World War II standards, the exploits of Eddie Chapman, a professional Soho criminal turned double agent for the Germans and the British, are extraordinary. His is a spy drama in the classic manner, complete with secret codes, invisible ink and parachute drops, cyanide capsules, sexy blondes (named Dagmar, no less) and a dashing hero. One of his girlfriends thought Eddie looked like Errol Flynn; certainly Flynn could have played him. He was an adventurer with a smile. Ben Macintyre says he could look you “straight in the eye” while he picked your pocket.

Related ‘Agent Zigzag,’ by Ben Macintyre: Service and Lies: A Spy Plays Two Sides (September 12, 2007) First Chapter: ‘ZigZag’ (October 28, 2007) Obituary: Eddie Chapman, 83, Safecracker and Spy (December 20, 1997)Chapman has surfaced before. In 1954 he published “The Eddie Chapman Story,” memoirs so eviscerated by the Official Secrets Act that his work for MI5 is not even mentioned (a gap that led some readers to conclude he had been only a German spy). A 1966 update, “The Real Eddie Chapman Story,” tells more, but guardedly. This book led, in turn, to a dim 1967 film, “Triple Cross.” And during the postwar years, readers of the London press could follow the wealthy “gentleman crook” through a series of escapades.

By the time of his death in 1997, however, Chapman’s notoriety had faded. Then, in 2001, MI5 declassified his file, with more than 1,700 pages of interrogation transcripts, internal memorandums and radio intercepts — a trove of detailed information, catnip to anyone interested in wartime espionage. To Ben Macintyre and Nicholas Booth, both seasoned London journalists, the chance to tell the full Eddie Chapman story at last proved irresistible. Here were all the makings of a popular book. Or, as it happened, two.

Nothing goads a reporter more than finding someone else chasing the same leads, so one can only imagine the urgency both authors must have felt as they went about tracking Chapman, dipping into the same archives, interviewing the same people, verifying the same facts, all this duplicated effort to tell essentially the same story. (One imagines further the urgency of their publishers juggling release dates.)

There are minor points on which they disagree: for example, Booth thinks Eddie may have met Churchill (as Eddie claimed), while Macintyre thinks this is “completely untrue.” But the accounts don’t contradict each other in any substantial ways. The differences lie more in emphasis and tone. Eddie’s widow, Betty Chapman, gets more attention from Booth, who says he had her full cooperation. Macintyre fingers Eddie’s last handler at MI5, Michael Ryde, as a villain and nemesis; in Booth he scarcely makes an appearance.

Whatever feelings of rivalry there may have been didn’t end with publication in Britain (where Booth was serialized in The Daily Mail and Macintyre in The Times). In a nice bit of literary one-upmanship, both of these American editions have been expanded to take account of recent information. When Booth’s book was already in type, Betty suddenly remembered a series of tapes Eddie had recorded before his death; the tapes were duly found in an attic and are discussed in an afterword. Macintyre was equally lucky: after the publication of his book, a filmmaker gave him six hours of footage with Eddie reminiscing.

Since few readers are likely to read both of these books, it falls to the reviewer to answer the inevitable “which one?” question. Macintyre is the more graceful writer; “Agent Zigzag” has a clarity and shape that make it the more fluent account. He is also the more skeptical investigator, less likely to take Eddie’s word, and he is more seriously interested in Eddie’s psychology and tangle of emotions. And it’s he who tells us that Eddie’s cellmate and pal Anthony Charles Faramus ended up as Cary Grant’s butler.

But Booth has done his homework, too, and his access to Betty offers interesting intimate details, particularly about the postwar years. So even though I would give a personal nod to Macintyre’s as the better book, the truth is that a reader could have a good time with either. The story, no matter who’s telling it, is a humdinger.

The broad outlines are these: Kicked out of the British Army at 18 (for going AWOL with a girl), young Chapman was drawn, moth to flame, to the louche nightclubs of Soho, table hopping between Ivor Novello and Noël Coward, and pursuing a flashy life supported by petty crime. (Macintyre is particularly deft on the tawdry glamour of this period.) One crime — theft, fraud — led to another, and finally to Chapman’s tabloid fame as the chief safecracker in the Jelly Gang (so named because they blew things up with gelignite, a skill that Eddie would find useful in his later career). When Scotland Yard finally caught up with him in 1939, Eddie was on holiday with Betty on the island of Jersey — he looked up from dinner to see the police approaching, dived through a plate glass window and ran down the beach. Betty didn’t see him again for nearly six years.

Those six years, of course, are the heart of the story. Captured and sent to prison in Jersey, he was still inside when the Germans occupied the island in 1940. He schemed to get back to Britain by volunteering to work for the German secret service, and the Germans agreed to train him as an agent and saboteur. Assigned to blow up the De Havilland aircraft factory, he was parachuted into Britain, where he immediately turned himself over to MI5. After an exhaustive vetting, he became double agent Zigzag. An explosion was faked at De Havilland, with the help of the legendary Jasper Maskelyne, a professional magician turned camouflage wizard. Berlin was pleased.

Related ‘Agent Zigzag,’ by Ben Macintyre: Service and Lies: A Spy Plays Two Sides (September 12, 2007) First Chapter: ‘ZigZag’ (October 28, 2007) Obituary: Eddie Chapman, 83, Safecracker and Spy (December 20, 1997)After that, as they say, it was one thing after another. Eddie returned to the Continent via Lisbon, was awarded an Iron Cross by a grateful German intelligence service (the only British citizen ever to receive one), then went to occupied Oslo, where he spied for Britain and went sailing with his newest girlfriend, Dagmar Lahlum. In 1944 he was sent back to Britain to report on the effects of the V-1s. Once more, he performed useful work for the British, deceiving the Germans about a fantastical weapon supposedly to be used against U-boats. As the war ended, MI5 got him an unofficial police pardon for his old prison charges and cut him loose, watching with some trepidation as he drifted back to the demimonde of Soho. There followed fixed dog races and a smuggling scheme in Morocco, but somehow Eddie managed to stay one step ahead of the law, flourishing again in nightclubs and driving a Rolls-Royce.

A review cannot possibly convey the sheer fun of this story, with its cast of eccentrics, its close calls and its improbable twists. Or the fascinating moral complexities. Consider the bond between Eddie and his German handler, Baron Stefan von Gröning, in some ways the central relationship of the story. Eddie felt affection and respect for him, even when he was betraying the baron. Von Gröning saw Eddie as a kind of son, though he embezzled part of Eddie’s pay.

It is unlikely, though, that Eddie would have minded much, had he known. In both these books he has the insouciant amorality of a natural crook and the restlessness of a born adventurer. He could lie instinctively, he knew how to protect his flanks and he was fearless; he had everything, in fact, a successful spy should have.

And his life has everything a successful spy story should have. This is the way such tales used to read, before spies became disappointed bureaucrats waiting for their pensions. They won the war and got the girl and maybe even ran a scam on the side. Could it ever really have been like that? “Agent Zigzag” and “Zigzag” suggest it may have.

AGENT ZIGZAG

A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal

By Ben Macintyre.

Illustrated. 364 pp. Harmony Books. $25.95.

ZIGZAG

The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double Agent Eddie Chapman.

By Nicholas Booth.

Illustrated. 386 pp. Arcade. $26.99.